Chapter 15: Ostracism and Realignment, 1945-1950

"The Franco regime was judged not only in light of wartime policy but as much or more in terms of its origins during the Civil War, which had depended on German and Italian assistance. As a military dictator, Franco also reflected a much more clear-cut “fascist image” than Professor Salazar. His government was commonly described as the last fascist regime in Europe, and for the first year or more after the war was showered with rhetorical abuse and roundly denounced on almost every hand. Any distinction between Francoism and Hitlerism was generally ignored.

To this the regime responded with an air of outraged dignity, insisting on its own independence and originality and stressing the salient role of Communists in promoting the most virulent forms of hostility against it. Yet it did little good to denounce the hypocrisy involved in demonizing Franco while blithely accepting the expansion of totalitarianism through- out most of eastern Europe, for in 1945 few cared to listen. Antipathy was so intense in France that Spanish workers who had been employed in German factories were subjected to severe physical assault while being repatriated across France. Denied entrance to the United Nations, the regime was ostracized politically and militarily, while Spains suffering economy was cut off from the international credits and opportunities necessary for more rapid regrowth. Though none of the western powers was willing to take up arms against the Madrid government, the domestic opposition was encouraged to carry out that task itself."

Revival of the Opposition

"The first small Communist units began to filter across the border in June 1944, alerting the Spanish authorities, who moved police and troop reinforcements to the northeastern border. Larger units crossed the Pyrenees into Navarre and into eastern Guipuzcoa in October, but gained little support from the predominantly conservative rural population and were easily turned back. Spanish military commanders in some instances refused to recognize the Communist volunteers as regular soldiers and did not always take prisoners. The major effort was made by Communist units possibly totalling 4,000 (estimates vary) through the Pyrenean Vall d'Aran into Lérida, a largely rural Catalan province. Once more the “liberators” won scant popular support in a partially right-wing rural district, managing also to identify themselves with the atrocities of the Civil War by murdering several village priests. They were soon repelled by military and police forces. Most fled back into France, as had their counterparts in earlier attempts, but some made their way into the interior where they raised further recruits.

The anarchists formed guerrilla bands of their own, associated with the otherwise shadowy Agrupación de Fuerzas Armadas de la Republica Española (AFARE) that was organized in connection with the Republican government in exile. These operated in mountain districts, and some- times in the plains or urban areas, for about the next six years, their activities finally petering out toward the beginning of 1952. "

"Though the Ministry of Justice announced to the British and American embassies in April 1945 that penalties for crimes committed during the Civil War were being canceled and that the Tribunal of Political Responsibilities was being dissolved that same month,’ the renewal of opposition activity was accompanied by new repression. As indicated in chapter 11, security had been tightened in the middle of World War II when new laws for the court-martial of political rebels had been promulgated on March 29, 1941, and March 2, 1943. By their terms, any kind of organized political activity would be considered military rebellion, for the decrees fine print brought almost any act of defiance under sumarisimo proceedings. This was moderated somewhat and made more precise by a new Spanish penal code promulgated on December 23, 1944, but military courts continued to hold jurisdiction over opposition activity.

Though some Spanish jailers were said by those in prison to be showing greater consideration for leftist prisoners in anticipation of drastic political change, the regimes sense of danger at the same time produced a sharp increase in the number of executions during the late summer and autumn of 1944. Rumor had it that 200 or more political prisoners had been shot during August and September, and the director of prisons admitted to a British diplomat that 70 had been executed during the latter month.* On the recommendation of the papal nuncio, a petition for clemency was signed by all the Spanish bishops and submitted to the justice minister, Aunós, but had little immediate effect. The spate of executions began to peter out only in April 1945 when it became clearer that the regime would not have to face a major military challenge.

Wavering followers who had begun to abandon their blue shirts in anticipation of a change of regime began to rally to Franco once more when the growth of leftist activity seemed to indicate that the alternative was return of the Reds. A new paramilitary formation, the Guardias de Franco, was formed of the most fanatical young Falangists in August 1944. Franco also used indoctrinated Falangists to solidify the Army officer corps behind him, elevating a number of reservist officers from the SEU and the university Militia to regular commissions during 1944-45. Radical Falangists contributed directly to the renewed climate of violence by attacking known leftists on their own, occasionally with fatal results."

"The monarchist opposition launched its own campaign on March 19, 1945, when Don Juan, after sending a copy to Franco, issued his “Lausanne Manifesto’ from his Swiss residence. This defined the system that the heir to the Spanish throne would henceforth advocate: constitutional monarchy. The monarchy would stand as the moderate, nonleftist but potentially democratic alternative to both the dictatorship and a radical new republic.

...Immediately after the manifesto, Franco convened the longest meeting of the Army’s Consejo Superior in the history of the regime, from March 20 to 22. Though there is no available record of the proceedings, it may be assumed that Franco repeated once more what he had already told the top members of the military hierarchy: that a properly installed and structured monarchy would be the logical succession to the regime, which he would in due course prepare, but that such a monarchy must not reject the principles for which they had fought, and that continuity could be maintained at this perilous moment only through his continued firm leadership, which was already planning new institutional reforms. He was apparently assured of the full support of the military, who respected his shrewd leadership of the armed forces, the firmness and equilibrium of his command, and his prudent diplomacy. They had little interest in abandoning their commander-in-chief for a liberal monarchist experiment during mounting international hostility and a powerful leftist offensive. "

The Reforms of 1945

"Franco realized that he faced the most fundamental turning point in the life of the regime, which had to be altered in some ways to survive in the postwar world of social democratic western Europe. There is no indication that he ever thought of abandoning power. If he did, the fate of Mussolini and the vigor of the purges in France and the Low Countries only served to dissuade him. The caudillaje, once undertaken, was a life-and- death enterprise. As he told a leading general, “I shall not make the same mistake as Primo de Rivera. There will be no resignation: from here only to the cemetery.’

By the spring of 1945 Franco had a fairly clear design for his future course. Fundamental new laws would have to be introduced to give the regime more objective juridical content and provide some basic civil guarantees. A major effort would be made to attract new Catholic political personnel and intensify the Catholic image of the regime in order to win the support of the Vatican and reduce the hostility of the democracies. The Falange would be deemphasized but not abolished, for it was still useful, and no rival political organizations would be tolerated, though to some extent censorship might be eased. A municipal government reform law would be promulgated, and ultimately a new statute to legitimize the regime as a monarchy under Francos regency would be submitted to popular plebiscite.”"

"The Fuero de los Españoles, its title employing the neotraditionalist language (reminiscent of medieval fueros or specific local rights) so dear to the regime, was promulgated on July 17, 1945. It was based in part on the Constitution of 1876 but pretended to synthesize the historic rights guaranteed by traditional Spanish law, and guaranteed many of the civil liberties common to the western world, such as freedom of residence and cor- respondence and the right not to be detained more than seventy-two hours without a hearing before a judge. Castiella was apparently responsible for adding article 12, “Every Spaniard may express his ideas freely provided that they do not attack the fundamental principles of the State,” and article 16, “Spaniards may gather together and associate freely for lawful purposes in accordance with the stipulations of the law.” This worried Arrese, but the freedom pledged by these sections was curtailed in article 33, which stated that “the exercise of the rights guaranteed in this Bill of Rights may not attack the spiritual, national, and social unity of the country,” while article 25 permitted them to be “temporarily suspended by the government’ in time of emergency.”"

"On September 3 Franco received a letter from Serrano Súñer empha- sizing that the regime must be reorganized on a broad national-unity basis to include representatives of “all non-Red Spaniards,” that the Falange must be dissolved and a plebiscite conducted to legitimize the monarchy. Contrary to his usual habit of ignoring criticism, Franco soon afterward received his brother-in-law for a long and frank discussion, their first in three years, and revealed more than a little uncertainty about how to proceed.”

During cabinet meetings in September and October Franco seemed to support Martín Artajos point of view against the resistance of Girón and Rein Segura. A series of limited reforms were discussed, such as an amnesty for Civil War crimes, electoral reforms of the Cortes, a relaxation of censorship, and a referendum law. At times Franco sounded as though he really believed in a system of checks and balances, observing, for ex- ample, that Nazi Germany suffered catastrophe through “the decision of one man” and that the same danger existed in monarchies which could “lose their way if the king only looked into the mirror.”

Yet the changes that emerged in following months were piecemeal, minimal, and in some respects merely cosmetic. The most influential voice counseling Franco to change things as little as possible was that of Carrero Blanco. In one memorandum, Carrero stressed that the regime must above all rely on “order, unity, and staying the course [aguantar],”” and so it did. On October 12 new proposed legislation was sent to the Cortes that would slightly liberalize the terms of meetings and associations and individual civil guarantees, in accordance with the Fuero de los Españoles. New municipal elections were announced for the following; March, with members of city councils to be chosen through indirect procedures (one-third by heads of families, one-third by the syndicates, and the remaining third by those already selected through the first two channels), though the government would continue to appoint all mayors directly. On October 20, an amnesty was announced for prisoners serving sentences for Civil War crimes, and two days later a new Law of Referendum was announced which provided that issues of transcendent national concern would be submitted to popular referendum at the discretion of the government."

"Franco, however, was clear in his own mind regarding its value. In an earlier conversation with Martin Artajo, he had observed that the Falange was important in maintaining the spirit and ideals of the Movement of 1936 and in educating political opinion. As a mass organization it had the potential to incorporate all kinds of people, and it organized the popular support for the regime that Franco insisted he saw on his travels. It also provided the content and administrative cadres for the regime’s social policy and served as a “bulwark against subversion,” for after 1945 Falangists like Munoz Grandes had no alternative but to back the regime. Finally, the Caudillo observed somewhat cynically, it functioned as a kind of lightning rod and “was blamed for the errors of the government,” relieving pressure on the latter.* Franco declared that it was merely a sort of administrative “instrument of national unification”* rather than a party. Further fleeting clandestine activities by a handful of activists who resented their new subordination could largely be ignored.”"

"The construction of a “cosmetic constitutionalism,” as it has been called, was for the moment completed by publication of a new Cortes electoral law on March 12, 1946. It changed very little, maintaining the principle of indirect and controlled corporative elections, but provided for representation from municipal councils and increased syndical participation. None of these reforms amounted to any fundamental institutional change in the regime, but they did begin the elaboration of a facade of new laws and guarantees which its spokesmen could refer to in terms of political representation and civil rights, however stark the contrast with reality."

The Nadir of Ostracism

"Throughout 1945-46 the regime mounted a press and publications campaign to try to convince foreign opinion that the Spanish government was essentially a system of organic Catholic institutions and had never really been committed to or believed in the victory of the Axis. "

"None of this had much effect. The captured archives of the Third Reich yielded considerable evidence of the regime's association with Germany,* and many wild rumors went far beyond fact. One French intelligence report had it that 100,000 Nazis and collaborators were being sheltered in Spain, while Soviet spokesmen at the United Nations charged that 200,000 Nazis had escaped to Spain, adding that atomic bombs were being manufactured at Ocaña, 70 kilometers from Madrid, and that plans were afoot to invade France in the spring of 1946. As new elections ratified the power of the left in western Europe, antipathy to the Spanish regime only increased, and on November 20 the United States ambas- sador abandoned Madrid, leaving the embassy in the hands of the chargé d affaires."

"Within Spain the international campaign against the regime was energetically depicted as inherently anti-Spanish, a foreign left-liberal conspiracy to tar the entire country with a new Black Legend. The role of Soviet and Communist forces, such as the Soviet-dominated World Federation of Trade Unions, was played up to the fullest extent"

"There is little doubt that much of moderate Spanish opinion rallied to the regime during its period of ostracism. The largest disaffected strata were as usual industrial workers and the poorest or the landless peasants. Nearly all Catholic opinion, which in 1945 accounted for more of Spanish society than it had a decade earlier, supported the regime. This included most of the northern peasantry and much of the urban middle class. To what extent the non-Catholic middle class actively supported the opposition is less certain. The regime in general continued to count on the same social strata, groups, and regions on which its military victory had earlier been based. "

"The French government temporarily closed its Pyrenean border in June 1945 and closed it indefinitely on March 1, 1946. This action was taken immediately following the Franco regime's execution of Cristino García, one of the Communist guerrilla chiefs it had apprehended, who happened also to be a French resistance veteran. "

"Churchill delivered his famous Iron Curtain speech in Fulton, Missouri. To Madrid, this indicated that, as they had hoped for and expected, the western powers were beginning to take note of other and graver concerns more consistent with the regimes own alignment.

Moreover, it had become clear particularly in the case of the United States, the power about which Franco was most concerned, that moral and political condemnation of the regime was not being allowed to stand in the way of major economic and transportation interests. Though Washington had announced that suffering Spain would be at the bottom of its general list for scarce postwar exports, it had included Madrid in the development of the transportation and communications network led by the United States. "

"There was no relaxation of pressure during 1946. The report of a special subcommittee of the United Nations Security Council declared that “the Franco regime is a fascist regime’ and found it a “potential,” though not an “actual,” “menace” to peace, despite the extreme weakness of the Spanish armed forces and the complete absence of any encouragement of terrorists or subversive activity beyond its borders. Finally, on December 12, the General Assembly voted 34 to 6, with 13 abstentions, to advocate complete withdrawal of international diplomatic recognition from the Spanish regime if a representative government were not soon established in Madrid."

Hispanidad: The Latin American Connection

"Though Mexico and several other Latin American states were intensely hostile to the regime, Spanish diplomacy was nonetheless able to find its strongest support during the ostracism from a number of sympathetic Latin American governments. "

"Ever since the first organization of radical Spanish nationalism emerged in 1931, it had been made clear that there was no ambition to reconquer or colonize Latin America, but to restore close relations and achieve a position of hegemony for Spain."

"but formal pronouncements that Spain harbored no designs of political domination in the western hemisphere” were not accepted at face value in Washington. "

"The new Argentine government of Juan Perón provided the Spanish regime with crucial backing during the decisive years 1946-48. Leader of a new Argentine “social nationalism” that sought independence from the existing international framework, Perón regarded the Spanish system as a kind of distant brother with similar international goals and problems. He soon defied the United Nations ban and named a new ambassador to Madrid, demonstrating that at least one prosperous exporting country was willing to come to Spains assistance. At their high point in 1948, imports from Argentina provided at least 25 percent of all goods brought into Spain and for two years guaranteed vital foodstuffs for a hungry population. Though Argentine assistance declined to a much lower level of loans and credits in 1949 as the Perón regime encountered mounting economic problems of its own, for two years its role was almost indispensable.”

Latin American support began to pay further dividends as a group of Latin American representatives worked in the United Nations to end the policy of ostracism.” "

The Apex of National Catholicism

"Though the regime’s strong Catholic identity was exploited more than ever to distinguish Francoism from fascism, the Generalissimo had been somewhat disappointed by the development of relations with the Vatican since the Civil War. Franco had hoped for an official concordat soon after the fighting ended; his government officially abolished divorce in September 1939 and resumed the state ecclesiastical subsidy (canceled by the Re- public) two years later. The Vatican, however, was leery of a formal relationship with the Spanish regime after its experiences with Germany and Italy, so that the first general agreement that had been worked out in 1941 fell well short of a concordat. "

"The decade of the 1940s brought marked revival of most aspects of religious life. Church attendance increased greatly, church buildings were re- constructed on a large scale, and virtually every single index of religious practice rose. By 1942 a new series of “popular missions” of mass evangelization were in full swing, continuing for more than a decade. In large industrial cities such as Barcelona sometimes nearly a quarter of a million people lined the streets during mission campaigns. Seminary facilities were expanded throughout Spain, though the number of new seminarians did not increase markedly until about 1945, after the new religious ac- culturation had had time to nurture young vocations."

"The primate Cardinal Gomá in fact found the results of the religious revival disillusioning, confiding to the British ambassador Sir Samuel Hoare (who was Catholic) that Francos triumph had not produced the true spiritual renewal that Gomá had anticipated. What it had produced was the “autocratic state,” the danger of which Gomá had overconfidently rejected in 1937. Catholic student associations were absorbed into the Falanges SEU, Catholic social groups repressed if they competed with state syndicates, priests forbidden to use the vernacular in Catalonia and the Basque provinces (despite Gomá's intercession), and a pastoral of the primate himself suppressed as too indulgent of the opposition and obliquely critical of the government.” Even the pope had been censored, as in the suppression of Pius XI's anti-Nazi encyclical, Mit brennender Sorge, and the excision of part of his radio message of April 15, 1939, felicitating the Nationalists on their victory but also urging kindness and good will to the defeated. Goma died in August 1940 a politically disillusioned prelate."

"By the last years of World War II, opinion within the Church hierarchy grew more divided. The clearest opposition to the regime was expressed by Fidel García Martínez, bishop of Calahorra, who issued strongly andcategorically anti-Nazi pastorals in 1942 and 1944. A few other bishops began to issue what were termed “social pastorals” that condemned the abuses and injustices of the prevailing economic structure, particularly in the countryside. These culminated in the first collective social pastoral by the bishops of eastern Andalusia in October 1945, which recommended separate worker and management associations to replace the state vertical syndical system."

"Though Catholic publications were given greater liberty after 1945, they were not entirely free of restrictions either. Moreover, the new Hermandades Obreras de Acción Católica (HOAC; Worker Brotherhoods of Catholic Action), founded in 1946 to foster Catholic social concerns among workers and strongly supported by the primate himself, were harassed by the Syndical Organization and sharply censored.”"

Legitimization as Monarchy

"The Generalissimo maintained contact with Don Juan through personal intermediaries during the autumn and winter of 1945-46 and decided not to oppose the Pretenders plan to move his residence to Portugal. Franco apparently believed the move might facilitate an interview which he could use to his own advantage, and therefore he indicated approval to

the Portuguese government. On February 2, 1946, Don Juan took up residence in Estoril, a stylish suburb of Lisbon, establishing a base as close to Spain as possible. Once there, he showed no interest in visiting Franco on the latter's terms, while the Salazar regime granted him full autonomy and did not permit Franco's brother Nicolás, the long-term Spanish ambassador, to supervise his activities. Moreover, his arrival in the peninsula immediately sparked rumors of a new agreement with Franco that produced a letter of support signed by no less than 458 members of the Spanish elite, including two former Franco ministers (Galarza and Gamero del Castillo)."

"At this point Don Juans chief political advisor was Gil Robles, the Catholic leader who had supported Franco during the Civil War but subsequently turned against him for maintaining a permanent dictatorship. Gil Robles hoped to appeal to both the left and right wings of the opposition, first attempting to consolidate the support of a number of major Carlist figures who had recently rallied to the Pretender. The resulting “Bases institucionales de la Monarquía española,” issued at Estoril late in February, contradicted the Lausanne Manifesto, reserving considerable power for the king and postulating a largely corporative form of parliament, only one-third of which would be chosen by direct election.” The Bases did, however, promise a national plebiscite on the restoration of the monarchy as well as some decentralization of government.

Gil Robles then tried to gain the support of the non-Communist left for the holding of such a plebiscite as the first step in creating a practical alternative to Franco. Since the new Bases seemed to indicate that Don Juan was far from committed to a democratic, directly elected parliamentary system, the Republican government-in-exile rejected this proposal, though negotiations continued for some time with the Alianza Nacional de Fuerzas Democraticas, representing all the clandestine left-liberal opposition inside Spain except the Communists. Two years of complex dickering and maneuvering between the monarchist right and the non- Communist left followed. There were sporadic efforts to mediate by the most active and persistent of the military conspirators, the indefatigable Aranda, until Franco interrupted Arandas inveterate plotting by sending him off to two months of internal exile in the Balearics at the beginning of 1947.”"

"As the months passed, Carrero Blanco urged Franco to make use of the wave of popular support for the government being created in 1946-47 (some of it genuine) to proceed with setting up a workable monarchist succession strictly on his own terms.* Such a move would seize the initiative from the monarchist politicians and ratify Francos existing powers, yet legitimize them by converting the state system into a monarchy. Moreover, announcement of the Truman Doctrine on March 12, 1947, inaugurating the first official phase of western resistance to Communist expansion, began to open prospects of a polarized international situation which a re- legitimized Spanish regime might exploit to end the prevailing ostracism."

"The new Succession Law was ready by March 27. Its first article stipulated, “Spain, as a political unit, is a Catholic, social, and representative state which, in keeping with her tradition, declares herself constituted into a kingdom.” The second specified, “The Head of State is the caudillo of Spain and of the Crusade, Generalissimo of the Armed Forces, Don Francisco Franco Bahamonde.” The Spanish state was thereby declared to be a monarchy which Franco would govern until his death or “incapacity. ” He would have the right to name his royal successor for approval by the Cortes. The future king must be male, Spanish, Catholic, and at least thirty years of age, and must swear to uphold the Fundamental Laws of the Regime and of the Movement. There was no mention of any legiti- mate dynastic right of succession in the royal family until after Franco had designated a royal successor, whereas the law reserved to him the power to cancel the right of succession of any member of the royal family in the event of “notorious departure from the fundamental principles of the state.*"

"This legislation was designed to formally legitimize the Civil War caudillaje, recognizing Franco as the supreme organ of the state who could not be relieved of his powers without the action of two-thirds of the government ministers and two-thirds of the Council of the Realm, followed by a two-thirds vote of the Cortes. Since all the members of these bodies had been appointed either directly or indirectly by Franco, this was an altogether implausible prospect unless he were to fall into a prolonged coma."

"Carrero Blanco delivered the text of this new legislation to the Pretender in Estoril on March 31, only hours before Franco announced it to the nation. This aroused rage and consternation within the royal circle, for it went even further than the project of an authoritarian reform and instauración of the sort proposed by Acción Española under the Re- public, making the succession elective and dependent on the pleasure of a military dictator. On April 7 Don Juan launched a public manifesto which began, “Spaniards: General Franco has publicly announced his intention to present to the so-called parliament a Law of Succession to the Head of State, by which Spain is constituted as a kingdom and there is projected a system completely opposed to the laws that have historically regulated the succession to the Throne.”” The manifesto took a strong stand on the principle of hereditary succession, emphasizing that the new system adopted a principle of election based neither on the royal dynasty nor on a truly elected parliament. The Carlist leader Don Javier de Borbón- Parma also protested in a personal letter to Franco. Both these messages were of course completely suppressed within Spain. Through the media of the Movement the government immediately launched a campaign against Don Juan as an enemy of the regime and of Spain. "

Waning of the Opposition Offensive

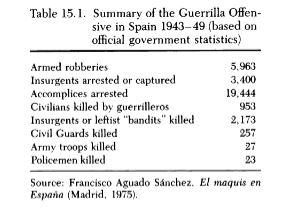

"The regimes success in counterinsurgency was due to several factors. Though the paramilitary Civil Guard did most of the police work and fighting, sizable military forces were also committed. Large-scale Army deployment gave the counterinsurgency the heavy preponderance of man- power necessary for success, making it possible to control the countryside without disruption of civilian life. Moreover, many of the mountain and forest regions of the north which were most propitious for guerrilla operations were inhabited by conservative, Catholic farmers not disposed to shelter or support the insurgents. Though some sanctuary was available to insurgents in southwestern France, its extent was eventually reduced by French authorities."

"The strike activity of 1946-47 was centered in the Basque provinces and Catalonia, reaching a climax in a major industrial walkout in Vizcaya that began on May 1, 1947. The state syndical system in the province broke down, and within three days at least 60,000 workers had left their jobs. Stringent measures were taken by the police and employers to break the strike. There were reports of as many as 7,000 workers temporarily arrested and another 14,000 fired from their jobs,* though these figures may be too high. Such tough measures achieved their goal. Unsupported by effective political activity elsewhere or any dent in the regimes internal unity or mechanism of repression, worker dissidence began to subside after 1947.

Though armed repression was left to the Civil Guard and armed police, juridical prosecution of political dissidence remained the province of military courts. All pertinent legislation in this area was recapitulated by a new Ley de Represión del Bandidaje y Terrorismo (Law for the Repression of Banditry and Terrorism) announced on April 17, 1947.

Some thousands of leftist prisoners were still under detention and there were still occasional executions, though normally only of those convicted of delitos de sangre (crimes of blood, usually killings). An occasional leftist militant died under police beatings. "

"Francos success in the 1947 referendum that made the state a monarchy accelerated the division of the opposition political groups. In July, the Socialist party abandoned the Republican government-in-exile to attempt an understanding with the monarchists. Most other emigré parties began to follow their example, condemning the Republican government to the merest shadow of an existence in exile. Yet the ensuing Socialist- monarchist entente was ineffective and soon broke down. Gil Robles, the chief monarchist advisor, more or less admitted that under the circum- stances which they faced, new maneuvers of that sort were virtually hopeless. The regime felt sufficiently secure to hold the first public trials of oppositionists—fourteen students—in Madrid that summer.

The armed opposition was still capable of action, and on several occasions in 1948-49 there were gunbattles even in the streets of Barcelona with anarchist urban guerrillas, but the insurgency grew steadily weaker and more isolated. A decree of April 7, 1948, finally ended the general terms of martial law that had been in effect since the Civil War, though all political offenses of any magnitude would continue to be tried by court- martial. In November, the government felt secure enough to implement a reform announced three years earlier, holding the first indirect corporative municipal elections. Such a controlled process involved no political risks, though in a note to Franco the foreign minister lamented the clumsiness of the first official announcement, which as he put it “unnecessarily reveals the limited character of the voting."

Rapprochement with Don Juan

"Franco had intermittently sought a meeting with Don Juan for more than two years, and one was finally arranged on the Caudillo's yacht Azor off San Sebastián on August 25, 1948. The resulting three-hour conversation was not fully congenial, for Franco tended to treat the heir to the throne as a political ignoramus uninformed on conditions inside Spain. Nonetheless, Don Juan felt that he had no choice but to agree to a political truce. Franco explained that his own work was not yet completed and that a quick restoration would be desirable only in the event of a war with the Soviet Union (in which case Franco would have to assume active command of the military) or of national economic bankruptcy, a contingency that seemed equally unlikely. Franco promised to put an end to the propaganda against the royal family, and Don Juan himself suggested that it would soon be appropriate for his oldest son and heir, the cherubic, blond, brown-eyed Prince Juan Carlos, to continue his personal education inside Spain. Franco readily agreed to this, for it opened the possibility of training a younger eventual Bourbon heir within the framework of the regime itself.”

The ten-year-old prince arrived in Spain on November 7, 1948, to begin a difficult role.'% Franco did not entirely make good on his pledge to eliminate antimonarchist propaganda, for he did not supervise the Movement very closely and he did not insist that its bureaucrats eliminate all expression of antimonarchist sentiment. Juan Carlos would encounter a great deal of intermittent hostility from some members of the regime during the next decade. It was during these adolescent years away from his family and in an uncertain environment that he developed the somewhat melancholy expression that later became familiar.

On September 19, 1949, after Juan Carlos had been in Spain ten months, his father wrote a strong letter to Franco threatening to withdraw his son, since the regime was doing little to favor the monarchy. Franco, as usual, did not reply for a full month,"

The End of Ostracism

"The regime sustained its own informational counteroffensive through- out this period,'* emphasizing that Franco had been the first and most vocal to warn of the dangers of Communist expansion in Europe. In numerous government statements and in several official interviews of Franco with foreign journalists, the regime advertised its availability for a western anti-Communist alliance, a project in which the Spanish leadership, as it was pointed out, had more experience than any other.

At the United Nations General Assembly session of November 17, 1947, a Soviet-inspired initiative which would have authorized the Security Council to take some sort of unspecified action against the Spanish regime failed to carry by the necessary two-thirds. Among those voting against it were the United States, Canada, Australia, and a large number of Latin American countries.'% This made it clear that the international policy of ostracism was weakening, and on February 10, 1948, France opened the Pyrenean frontier for the first time in nearly two years."

"In accordance with the Truman doctrine of assisting Greece and Tur- key against Communist pressure, the United States had begun to look for strategic support in the Mediterranean. In February 1948 Admiral Forrest Sherman, chief of United States Naval Operations, made an os- tensibly private visit to Madrid, where his son-in-law was naval attaché, in conjunction with a Mediterranean trip. There he also met with Carrero Blanco, ever eloquent in arguing the geostrategic importance of Spain. In the following month, Representative Alvin O’Konski of Wisconsin succeeded in adding an amendment to new legislation establishing an Ameri- can Marshall Plan for Europe that would have included Spain, but the Truman administration cut it out of the final bill.’”"

"The Spanish government undertook new initiatives that spring, negotiating commercial agreements with Britain and France in May. The slippery and astute Lequerica, dropped from the Foreign Ministry three years earlier, was given a specially created position, director of embassies, enabling him to take up ad hoc residence in Washington, where he helped to supervise a remarkably successful Spanish lobbying campaign over the next two years. Chief representative for the subsequently notorious “Spanish lobby” was the Washington lawyer Charles Patrick Clark (who at one point was being paid a retainer of $100,000 per year), though others like the firm of Cummings, Stanley, Truitt and Cross were also used.'* One of the first benefits was negotiation of a $25 million loan to the Spanish government from the Chase National Bank in February 1949"

"general American opinion was changing rapidly in 1948-49. A poll taken in Massachusetts during May and June 1948 reported that 30 percent of the opinion sampled was hostile to the Spanish regime, and a national survey in November showed 25 percent opposed to admitting Spain to the United Nations, while only 18 percent favored it. A Gallup poll at the end of 1949 reported that of the 56 percent of the sample interviewed who were able to identify Franco, 26 percent favored admission and only 18 percent were opposed.''' Such disparate samples could not in themselves produce reliable conclusions, but the obvious inference was borne out by other evidence as well. In 1945 a rally against the Spanish regime was able to assemble 16,000 in Madison Square Garden, but a similar rally in January 1950 drew a mere 1,000"

"Though the Truman administration at first refused to ratify the measure, the United Nations vote of November 4, 1950, which cancelled the terms of the 1946 ban on the Spanish regime, brought a reversal of government policy. On November 16 a loan of $62.5 million was approved, and at the close of December an American ambassador, the first in four and a half years, was named to Madrid. Spain would never be included in the Marshall Plan and under the Franco regime would never be invited to join the newly formed North Atlantic Treaty Organization, while entry into the United Nations would be delayed five more years. Nonetheless, by the close of 1950 the most severe aspects of the international ostracism had come to an end."